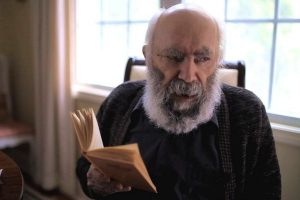

On September 23, 2018, we lost a colleague, literary scholar, poet, and co-founder of the New York Group of Ukrainian poets. Bohdan Rubchak’s scholarly and poetic contributions to Ukrainian literature still await serious studies and assessment. In the ensuing paragraphs I would like to share some thoughts on his life and work originally included in my book Literature, Exile, Alterity: The New York Group of Ukrainian Poets (2014).

Born in 1935 in Kalush, Western Ukraine, Bohdan Rubchak was barely a teenager when he arrived in America in 1948, together with his mother, settling in Chicago. His early proclivity for things philological eventually resulted in full-fledged literary and scholarly career. He graduated with a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Rutgers University in 1977. After almost a decade of living on the East Coast, he returned to Chicago in 1973 and took a teaching position at the University of Illinois. He worked as a professor in the department of Slavic languages and literatures until his retirement in 2005 after which he moved to Boonton, New Jersey, where he passed away.

The author of six books of poetry, numerous articles of literary criticism, and co-editor of the anthology of Ukrainian émigré poetry Koordynaty (1969), as a poet Rubchak defies hasty compartmentalization. On the surface, he easily strikes us as a traditionalist, the least experimental member of the New York Group, especially in the way he approaches poetic language and forms, but what is often missed is that behind his refined intellectualism and poetic craftsmanship lies a strikingly innovative incorporation of the implied reader into the structure of his texts. Rubchak appears to be the only poet of the group who displays a penchant for a playful dialogue with the reader. His early poems betray an existentialist bias and foreground the motif of dichotomy between nature and the city, but his more mature works favor intellectual, referential, distanced, and rational treatment of the subject matter over the guarded spontaneity and lyrical directness of his early poems. Rubchak’s poetry bears no references to American reality; by and large it basks in the universal rather than in the particular and the local. The poet does not question the validity of the accepted order of things, whether on the moral or the aesthetic plane, but he does like to reveal its shortcomings. His belief in the power of poetry, its transformative and almost transcendent quality, betrays the poet’s modernist posture. Previous styles, works, and traditions are played with, but never doubted; they are paraphrased, but at the same time cherished and accepted.

Maria G. Rewakowicz

Rutgers University – New Brunswick, NJ